“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.”

Rumi

I really didn’t realize the drastic effect of stress on my life until 2011. It was during the summer of that year I was driving to the dance studio where I’d worked for a decade and started to feel overwhelmingly frightened. My heart started racing, palpitating, my vision was blurry, and I felt I was losing control of my motor skills. A marked feeling of dread swept through my body. It was a feeling I’d only known twice before to this extreme degree: the morning my mother called me, telling me my father had passed from his esophageal cancer in the night, and that terrible morning on September 11, 2001. Heart attack? Was this it? The end of the line?

Within a few blocks of the studio, I pulled over, thinking in horror that I wouldn’t be able to make it to the nearest hospital. I had never been seized by such fear, such incredible disconcert, such powerful nihilism. Worse, it didn’t seem to be something I could maneuver out of through positive thinking or refocusing. It felt like a inner spiral, a dark and menacing vortex sucking down my interior landscape that I had no choice but to endure.

(L) With Louis van Amstel and my student, Ellen, not looking my best. 2014. (C) With Ellen, after a comp. 2014. (R) With long-time friend and mentor, Jacques de Beve, who sadly passed on during COVID, and Janice Kregor, my student of many years. 2010. Lexington Arthur Murray Dance Studio.

After 30 minutes on the side of the road, it subsided, but it left me in such a shocked and disrupted state, that I was afraid to start the car again. I called in sick to work and spent the next hour slowly driving the five miles home. I was bewildered for the next week, as I read things online, researched, tried to understand what might be happening to me. I found out very quickly the panic attacks I was having were common, though the experience of them differed slightly from person to person. Like tinnitus, these perturbances were body signals some people lived with and eventually learned to ignore, while others were apparently driven insane, many times to the point of no return. I played out many scenarios in mind during that time, thinking this could finally be it. What would people think? “Oh, Chip was sick? Chip died? Wow.” And then it would be back to business as usual. Odd, I thought, that even in the most dire and desperate moments, one can’t help but think about what others might think about your illness, your death, the device of your passing. But we know rightly enough that once they’ve thought on it for awhile, it’s back to business. It gives one the biggest admonition possible to live life your own, not caring what other people think about it. Or, as Christopher Walken says: “if you realized how quickly people forget you when you’re dead, you stop trying to impress them.”

I find my own protective ego layer is such that when I hear about friends and family who have died (which, of course, happens more frequently these days), there is the initial shock, but almost immediately it turns into a comparison of how they died in relation to my own mortality. What if it was cancer for me? Or a car wreck? Or diabetes? And while these projections and mirrorings to and of my fellow primates and their timely or untimely ends are much more understood in our world today, the kneejerk emotional response comes online, as evolution dictates, before any logical defense can be mounted or maintained.

With quintessential dance champion, Bill Irvine, and Phyllis Wilson. London, 2006. With Derek Hough in his “Footloose” days, and Phyllis Wilson. London, 2006.

Theatrical Bolero with Renee Gallagher. Dancing with the Lexington Stars, 2014.

More attacks came, with varying effect and duration. Certain things triggered them…driving, for instance. It seemed that a slight increase in stress by doing a generally more stressful activity was common to trigger the internal abomination at play in my psyche. And what was this specifically? The overactivity of my adrenal glands, flooding my body in the same way a “fight-or-flight” response would get triggered if I were running from a tiger. This, in turn, sets into motion a host of other gargoyles in the body. Lack of appetite, lack of sexual appetite, constricting of blood vessels, hair loss (a problem not unknown to me already), depression (the other side of the anxiety coin, by the way), dizziness, dread, senses dampened or delayed, just to list some of the fun. The problem was, there was no way to know when these would come about and I was especially in the dark about how to turn them off.

![]()

(L) With my first martial arts teacher, Dr. John Winglock Ng. 1984. (R) Then, in 2013.

The attacks got so bad that sleep was nearly impossible. To say the experience was a mid-life crisis would be an understatement, but there was every moment an unstoppable meditation on mortality that made even a moment’s peace out of the question.

I found, oddly enough, that when I eventually forced myself to go to work, I actually felt better. There was some bit of psychology in putting my focus on others. For the time I was doing so, teaching my students, I apparently couldn’t focus on myself. This opened the door to the first valuable lesson this taught me. To get out of my own head and to stop feeling bad were helped greatly by focusing on and being of service to my fellow creatures. It’s a fire I try to keep alight to this day.

Zig Ziglar once famously talked about having a leg injury that left him barely able to walk. He was scheduled to give one of his long seminars, and gave it, standing and talking and focusing on the material for over three hours, without feeling much pain. Then, when he was off-stage and out-of-site, he collapsed in a heap.

(L) With Soke William Durbin, my teacher and mentor for nearly thirty years. The most austere and compassionate man I know. 2014. (R) The Masters of Kiyojute Ryu Kempo. 2017.

Another lesson was that it was the particular type of stress that was contributing to these things. It wasn’t the volume of what I was doing in life, per se, it was the specific stressors. This came about through several discussions with a man I like to think of as a mentor, Nick Gargala. Nick had been a leader in The Mankind Project (aka “The New Warriors”), an organization I had been actively a part of since 2003. Nick and I had both served on many mens’ weekends, through which many men had come, most of which had incredibly powerful experiences, and developed better life skills and deeper meaning for themselves as a result.

(L) With John Kimmins, the President of Arthur Murray International. Not looking myself, at a low point in the depression/anxiety cycle. 2012. (R) Surrounded by the fairer sex, 2012.

It was Nick who I felt most like, and was most connected to. It was Nick who held me as I processed my father’s death in 2008, and whose leadership I most tried to emulate. However, in 2010, I left The Mankind Project, feeling my time with the organization had run its course. While there was no kind of ill will, I felt if I had to sit in another men’s circle and talk about my past or the reasons for my behaviors, I’d go crazy. I attributed some of this to something that many men in the group had voiced over the years, which coincides with a great deal of psychotherapy and admitted by some of its practitioners, namely that there can very easily be too much focus on the wound. Once a person realizes the problem, purging the emotional blocks connected with it, it should be time to get on with life. For some, there is still a picking at the scab decades later, and an inability to move into action and be fully present for family, friends, and the world. This is not a judgement, but an observation. Indeed, I still recommend men to MKP when the opportunity is right. Another valuable takeaway from the experience of my father’s death was this: don’t make major life-decisions in the wake of great tragedy or loss. Breaking this rule, which was unknown to me at the time, was what led me into my second marriage; a marriage with a woman fourteen years my junior. While the time between was no an issue in itself, the lack of interests, alignments, and philosophies was huge. Why didn’t I see it with all my vaunted personal work? It wasn’t that she was some horrible person, just not right for me. The only answer can be that our anxiety blinds us, makes us unable to see beneath the surface of the water, where 90% of the iceberg lives. With this new and added stress, my body began to feel sick, this was in the two years leading up to the major attacks. My point here is that these stresses had been deeply and unconsciously stirring for some time before I pulled over that day, thinking it to be my last.

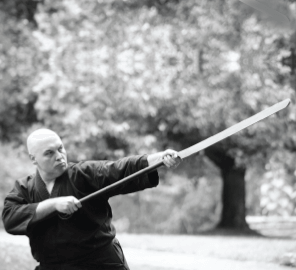

Promotional photos for Kiyojute Ryu Kempo and Honsho Kan. 2018.

Promotional photos for Kiyojute Ryu Kempo and Honsho Kan. 2018.

I had always been a reader and heavy consumer of material I deemed to be “thought-provoking” and “philosophical.” This existential dive forced upon me by these attacks sent me into as deep a plunge with what I was reading and taking in. Proust, Camus, Hume, Hitchens, Hobbs, Rousseau, Solzhenitsyn, Mann, and more of this ilk were all consummations devoutly to be wished, but in retrospect, I can’t say they were the best thing for my mental and emotional state at the time. Nor was revisting Bergman and Tarkovsky, though I can always do it for some reason. Taking in these formative works, by the way, is a much different experience than swallowing them in a collegiate way, with a paper due next week, trying to dig up relevant references and fit them into ambiguously-themed pieces that will be shelved forever, maybe even used to line birdcages everntually, as they probably should be.

It occured to me what I thought for sure to be true many years before, which was the dominant feeling or ethos in the body at any given time will cause the mind to seek out the like in the external. If you’re sad, you may very well end up listening to melancholy music, if you’re happy, it might be party music all day long. It seems, though, that many people get conscientious of their particular mien and tell themselves they must do the opposite, to balance the scales, as it were. I’ve found over the years that I’m not of this second tribe. I tend to go for the heavier stuff when my mood and state is heavier. So, I found myself listening to a lot of sad music. Philip Glass, Terry Riley, Scott Walker, Jacques Brel, Léo Ferré, and Richard Thompson, who in my opinion, is one of the finest songwriters to every hold a pen and guitar. When all the stress came and my dad was gone, I found myself scuba diving through his “Woods of Darney,” which I offer as the saddest song I know. And yes, I do include “Danny Boy” in that comparative list.

Promotional photos for Dancing with the Lexington Stars, the annual fundraiser of the Lexington Arthur Murray Dance Studio.

Promotional photos for Dancing with the Lexington Stars, the annual fundraiser of the Lexington Arthur Murray Dance Studio.

It seems appropriate here to mention that not everyone seems as prone to these issues with anxiety as others. Of course, none of us are in anyone else’s skin, so it’s an impossible position, empirically or theoretically. For those who do suffer the most, I would offer that having something to cling to is helpful. It became clear to me that the body sending you thousand-watt signals that something is disturbing it goes hand-in-hand with crises of mortality, faith, and oblivion. Regarding death, one can in a quippy way state: “what’s the big deal? I didn’t have consciousness, ergo ego, before my birth, why should I feel any different after my death?” For this quaintly animalistic view, I say it’s the “after death” part that can be so unnerving, as it’s unknown. It’s in the dissolution of the ego one spends a lifetime developing and nurturing, that the fear factor emerges; a phenomenon unexperienced prior to birth, as far as we know.

(L) A Theatrical Argentine Tango Routine with Clare Seagren. 2008. (R) Dancing with Astrid Wenke-Sebastian at a fundraiser. 2017.

(L) A Theatrical Argentine Tango Routine with Clare Seagren. 2008. (R) Dancing with Astrid Wenke-Sebastian at a fundraiser. 2017.

Anyway, my father, my new fiancée, soon-to-be wife, and finally the crash of 2008. At the time I owned real estate here in Lexington, and when the market shifted, selling it all off without taking unimaginable losses was impossible. I was stuck with the responsibilities of landlording, getting sicker by the day, with more attacks coming. It got to the point my perception of reality was surreal. Internal things I didn’t understand were breaking. My vision was more blurred than usual; I couldn’t hear as well and would often miss major chunks of conversations; sleep was non-existent; and there were several late-night trips to the ER, as I was trembling so badly and felt a total shutdown was imminent.

I was fortunate I had been training in martial arts, theatre, dance, and meditation for years. The breathwork and keeping exercise going as often as possible helped tremendously. As I talked with others in-person and online, who had suffered attacks, some of them for decades, I was grateful I had been training all those years and had at least something to hold onto.

As Polonius, from FORTINBRAS. Studio Players, 2000.

As Polonius, from FORTINBRAS. Studio Players, 2000.

The Watcher was a concept I originally encountered from a theatre teacher, and I had been incorporating it into my acting and dance classes for students who were further along for some time. When one is performing, whether public speaking, dancing, acting, doing martial arts, whatever, in front of someone, the mind projects another personality outside of the immediate space of performance. This is the Watcher, and when it gets dark and affected by stress, it can turn into the Judge or the Critic. This is the voice and feeling outside oneself that is constantly whispering or shouting about all the wrong things that are being done. It’s never quite right, and in the analysis after perfomance, there’s always “woulda, shouda, coulda.” Who knows where the voice comes from. In the men’s work, for those who cared to dive deep and figure out what was going on, it would usually be the voice of the parent that maybe was dark to begin with or turned dark through the inflection and coloring of the person in their own, perhaps misshapen view of the people who raised them.

My parents, Virginia and Charles Sebastian, 2006.

My parents, Virginia and Charles Sebastian, 2006.

So I developed several exercises collectively labelled: “kill the Watcher.” They have to do with hearing the voice, but not reacting. It’s this last part that’s pertinent to anxiety attacks. As attacks show up due to stress and not being on the unique path meant for you, the mind starts going into warp, and the thoughts become so loud and powerful, it seems that nothing will quiet it. The Watcher, stemming from the mind, can go into hyperdrive as well. So for some sufferers of anxiety and depression, the figure outside oneself, giving feedback for objectivity and logic, becomes a large, looming spectre to be feared. Looking back on these things, it’s clear the workings of them, but when you’re in the center of the maelstrom, nothing makes sense. It seems the body and mind, on a much deeper level than we yet understand, even with our current knowledge of the unconscious/subconscious, knows when one is being pulled from the path. Is the path predestined? Is it something you develop in your early years and the wisdom of the body marshals all forces to direct energy and focus to that purpose? I’ll leave it up to you, dear reader. But there has to be a reason we are so drawn to some things and not others, besides a simple cursory fascination. Following your bliss, however it manifests, seems essential to making the days, weeks, and years quality.

The irony in my particular case is that I had been working in these various disciplines, following my bliss, for years before, all of which lent their special wisdom to the whole scenerio, but even with those tools in hand, I was still frozen and at the mercy of my own body and mind. Like so many mind/body issues, including addictions, the mind can’t heal the mind, nor can one “logic” their way through the maze. It sounds like common sense, but with the many, many people I talked to during that time, who endured similar horrors, I did not find one who followed a recipe and “thought” through the maze.

Something should be mentioned here concerning formal education. My folks had not gone to college and mine wasn’t the type of household that would force the issue of higher learning. The belief that you had to have a degree to get anywhere was for my generation, the Gen-Xers, unquestionable. Fortunately, I didn’t need much persuading, and have continued pursuing academia for most of my adult life. This has resulted in three masters degrees, massage licensure, and many dance and martial arts certifications. I don’t need to state what most people these days know for sure: degrees do not guarantee employment or anything else. I only mention it here because I’ve realized in recent years that the effort in the collegiate realm was as much about seeming smart to myself and others as it was with the actual accrual of knowledge. The other realization is a very old idea: “he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.” Solomon was right in his observation. More knowledge, even the most useless, gives one the feeling of accomplishment or empowerment. It’s probably why Jeopardy’s so popular. Does this make a better life? I’m not so sure. I’ve been a professor and I’ve known many…to say they’re the life of the party or have lives that seem more meaningful due to especially obscurist academics doesn’t even have a slight tinkle on the bell of truth.

(L) Darcae (Amber) Pike, Cathya Franko, myself, Astrid. The lovely ladies of dance. (R) Promotional pic for Ballroom.

(L) Darcae (Amber) Pike, Cathya Franko, myself, Astrid. The lovely ladies of dance. (R) Promotional pic for Ballroom.

I only bring up academia here in deference to anxiety. I feel that in many cases it creates more, especially when the focus is on facts and knowledge versus understanding. This was a distinction the late Roy Masters made in many of his books and programs, and it has always made sense to me. Knowledge and the accumulation of facts, in contrast to understanding, where one has a clear idea of how to use this knowledge, to think outside the box, to see the whole system, not just the constituent parts. So learn all you want, but don’t expect knowing the year Napoleon died or the history of the Zither will help you with anxiety or depression. It’s a non-start.

One day in the kitchen, trying to force down food, my vision fractured into random, jagged shapes. My body had no control. I had always thought, perhaps due to my Baptist upbringing, that suicide simply wasn’t an option. Those who would do themselves in, or self-immolate, somehow had inferior minds, and that was never to be entertained in my own worldview. However, that day in the kitchen, as close to the bottom as ever, I understood what can drive someone to such thoughts. It was the desperate fear of my own non-existence that kept me from such a terrible deed, and the ever-so-slight hope that maybe, possibly I would be missed. It certainly wasn’t the ridiculous concept of “unforgiveable sin,” a depraved thought only the ancient and medieval church could come up with. I’ve always been ultra-critical of using guilt and fear as control methods for bevahior, and it’s for a very simple reason, aside from the obvious of being creepy: it doesn’t work and it creates a lot of guilty and fearful people. It’s a hateful thing for the church or any other group that sees itself as having some dominion over others’ lives to add more ill-feelings to families whose loved ones have decided to leave the veil of tears.

Teaching a Ladies-Only Self Defense Clinic, 2019.

Teaching a Ladies-Only Self Defense Clinic, 2019.

I had been doing kata for many years as part of my martial arts training. One day, after I found out a horrible and detestable woman who was renting a house from me destroyed much of the house, I came home with a full-fledged panic attack and the feeling that no matter how hard I tried I could not escape the feeling inside my body. The spinning mind, the overactive adrenals, the inability to turn it off: it’s a horrible thing for the mind to lose control of that which it governs. I did kata for over an hour, burning and sweating, heart pounding, and after the last fraction of energy was burned, I collapsed in a heap on the living room floor. I slept for a day. Such were the days in the valley of the shadow of death.

My body was amplifying everything, and it became clear that these things that were spinning me so much out of control had always been at work in my life. They had always been going, but in a very low-resolution, deep-humming way, that had become over the years, just the normal course. The extremely overactive frontal lobes had always been overactive to some degree and had been the cause of overthinking, overanalyzing, with paralysis and procrastination in life oftentimes following. The illness that I felt as the direct result of feeling like I was being made to do a lot of things I didn’t want to do, had always been there. The inner voice, telling me to, once again, in Joseph Campbell’s words, “follow my bliss,” had always done so. And I knew from an early age that deviating from that whisper would turn it into a scream. As the anxiety grew and the attacks pressed on, that banshee voice became unbearable.

I was able to find some slight bit of relief from EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization Response). This was done in several ways including audio before sleep was attempted. A company called Evolucid had created the best ones I found. The relief was slight, but with nothing else, like a cup of ice water after being in the Sahara for a week.

It was somewhere in 2011 I was talking with Nick and he mentioned to me that stress needs to be looked at like a giant board, full of red buttons, representing stressors. For some people, if you push the “relationship” button, it has no effect at all, but for others, it’s like kryptonite. In my more lucid moments, I started thinking about what my buttons were. Current marriage…definitely a stressor. Money…absolutely. Real Estate. Sadness and loss still felt about my dad…yes.

Awarding my mom here first Tai Chi Certification, 2009.

Awarding my mom here first Tai Chi Certification, 2009.

I had carried with me the powerful image, when my dad passed on, of a mountain. My life, as a landscape, as a canvas, with the mountains of my life standing firmly in the background. When my dad left…one of the mountains disappeared. The plates shifted. Oh, I convinced myself I was handling it, and went about my business, but the internal melancholy of the loss was sometimes too scary and stark to bear. It’s an image from my friend, Neil Chethik, in his book, Fatherloss, which is the book I always recommend to male friends going through the loss of dad.

Anyway, the buttons. I realized maybe I didn’t have too many pushed, but the wrong ones for me, personally. Over the next year, with a lot of effort, I dumped my real estate. My marriage was fizzling out due to our differences; we agreed on divorce and in 2012, we split. I kept processing my father being gone, and along with this, the realization that I didn’t have a man to look to, that I was the one. For me, a huge part of this process was the gratitude I had for having my father as long as I did, a blessing not even afforded to so many of my male friends. This gratitude extended to having my mother as well. I have no complaints and the contentment of this has assuredly helped speed the healing.

On an antique carousel with the fairest representative of the fairer sex. Ebbelwoi Fest in Langen, Germany. 2017.

On an antique carousel with the fairest representative of the fairer sex. Ebbelwoi Fest in Langen, Germany. 2017.

It was over the next two years my body began to level off. I was able to relax more and more. My Kempo training, my martial arts, and a lot of movement and exercise in general, was invaluable. I was able to do a little caffeine, which I had nixxed when the attacks started, as it’s the first thing everyone recommends you cut. It helped tremendously, but I was thrilled to get back to leaded, bit-by-bit. My eyebrows grew in fully. The palpitations and shakes were fewer and farther between, and sleep came round again.

This all left me with bewildered amazement at how the body can heal itself, even from the most bizarre of threats and circumstances. It also reinforced what I know and everyone knows, but none of us want to admit…we really don’t know that much, and even less about our own bodies and minds. While this happy admission to not knowing everything can leave one open to predators when one is ill, the admission has to be made somewhere along the line, nonethless. There are those who wait in the wings, watching carefully for those who might be in a dilapidated state, who might be emotionally low, and like circling buzzards, get excited at the smell of flesh and opportunity.

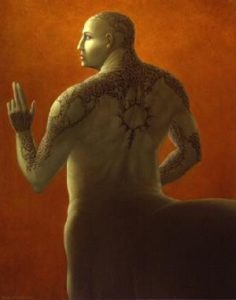

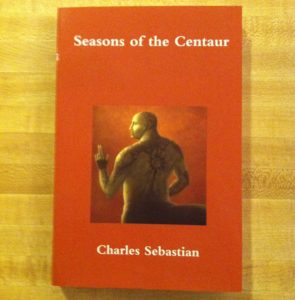

“Centaur” by British artist, George Underwood. George was kind enough to allow me to use the painting for the cover of my book of poetry, SEASONS OF THE CENTAUR, in which my homage to my dad, “Goodnight, my Father, Goodnight,” appeared. 2016.

“Centaur” by British artist, George Underwood. George was kind enough to allow me to use the painting for the cover of my book of poetry, SEASONS OF THE CENTAUR, in which my homage to my dad, “Goodnight, my Father, Goodnight,” appeared. 2016.

This happened when I went to pick out a casket for my father at a local funeral home, which shall remain nameless. The first and seemingly only room I was quickly whisked into had the most expensive, Cadillac-style coffins. The salesman gave the feeling of watching my body’s movements and measures, to see how far he could push into the upsell. He was crestfallen when I told him my dad grew up during the Depression and would kick my ass if I spent that much on a box that would be unseen in the ground forever. It turned out there were other, hidden rooms, after all.

Parts of this whole anxiety experience I’ve related to people in the years since that devastating time. If you’ve made it this far, I hope it hasn’t bored you too much. The main reason I wanted to set down these recollections and free-float them in cyberspace is for those who suffer. I remember when I went looking for answers or common experiences with which to gauge my own, and hopefully find some strategy to get back to health, there were few accounts. It’s my hope this will provide some help to those who may be searching, perhaps in the darkest place they’ve ever known, the mind spinning, uncontrollably.

(L) On the set of ALWAYS IN OUR HEARTS (PER ANNUM), with Director Don Simandl, and Fred Zegelien. 2021. (R) Shooting a scene with Brodie Lietch.

(L) On the set of ALWAYS IN OUR HEARTS (PER ANNUM), with Director Don Simandl, and Fred Zegelien. 2021. (R) Shooting a scene with Brodie Lietch.

I normally wouldn’t feel the need to spend so much time in this type of exposé. The nostalgia and remembrances seem to have a vacuum effect as the years roll on, people pass on, and memory somehow becomes an anchor into one’s reality and one’s life. There are many more pictures and anecdotes, but as I coined once in a class: “even the shortest memoirist can become the greatest dullard.”

My purpose in showing these bits of life in relation to the panic and anxiety is to drive home the importance of staying active, not squirreling away, frittering the days into nothingness. COVID has taught us that much, hopefully…that we need to get out and get on with it. This is something forever known to those who suffer attacks, though getting out and getting active can become impossible, at their worst. One can only do what one can do.

Know that stress is the root cause of your despair, whether managed or not, and deselecting the right buttons is the slow and steady balm you seek, though you may not yet know it. Part of me feels pretentious in even offering this monster anecdote, especially as disingenuous feelings can certainly appear to be a companion of true vulnerability. But staying open to these experiences and voicing them, bringing them out of shadow, somehow disempowers them. “What we do in dungeons needs the shades of day,” James Goldman says in The Lion in Winter, and so it is.

If shadow is driving us much of the time, though many may be loathe to admit, we know the one defense against its scourge is bringing things out into the light, disarming it, not being trapped into the same behaviors for decades-on-end for fear of criticism, or simply fear in general. To this I say, what other people think of me…is none of my business. And stealing from Mrs. Finney, my 7th-grade Social Studies teacher: FEAR…False Evidence Appearing Real.

I hope this account has been of aid to someone, perhaps even myself, though it’s unwise to ressurrect the defanged phantoms of the past too often. I’ll leave you with the poem below and the comforting phrase used most by the men of MKP, the phrase we all love and hate: “True Power. Giving up the control you think you have, and owning your truth.” May you all have truth and power in your lives, my friends.

Goodnight, My Father, Goodnight

I

Goodnight, my father, goodnight,

the long, dark trek is through.

Goodnight to you, brave knight,

till I one day am you.

Your beard hangs low, a grizzled gruff

upon that aged face.

Yet deep inside the finest stuff

kept from your marching days.

We bury you in Elysium-

among the gods to dwell.

Some see a grave and misty tomb;

I, a short farewell.

II

Goodnight, my father, goodnight.

You taught me all was good.

You took me to the spring at night,

you lead me through the wood.

You showed me all the plants to eat;

gave thanks for crops and deer.

You showed me yellow fields of wheat

before the harvest year.

You called me to the mountains gray,

where light and shadows cast.

“When my body finally leaves,” you said,

“what is left is what will last.”

III

Goodnight, my father, goodnight,

sleep well, my grand old knight.

Rest your weary, time worn bones

away from children’s sight.

And still there’s green upon the field;

a bird sings on the wing.

And children yet in woman sealed

From your tributary spring.

And I remember all, yes all,

as I prepare to die.

I’ve shown my sons the tomb and hall

where I’ll forever lie.

They remember all I told them here;

these memories of you.

You said ‘straight as the arrow flies,

man’s life should be so true.’

Goodnight, my father, goodnight.

Forgive what I have missed.

My sons move round to kiss that cheek

that years ago I kissed.