Chip Sebastian

The Skin of Our Teeth

PLAYWRIGHT BACKGROUND

Thornton Wilder’s background is as varied as his writing, and many of the early influences in his life find their way into his works. In 1927, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature for his novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey. He wrote six other novels in his long career, four of them prior to The Skin of Our Teeth. Wilder received two Pulitzer Prizes for Drama, one for Our Town, in 1938, and the last for “Skin,” in 1943.

Born in Madison, Wisconsin, on April 17, 1897, Wilder spent much of his youth in Hong Kong and China. Wilder’s father, Amos Wilder, was consul general for the United States in China. Amos Wilder moved his family to California and there the young Wilder was first introduced to theatre, when he attended Berkeley High School in 1909. Wilder acted in several high school productions when he attended the Thacher School in Ojai, California, in 1912. Acting was of interest to Wilder, but his writing efforts seemed to eclipse any notions of performance he may have indulged. He briefly considered playing the lead in Our Town, when it opened on Broadway in 1938, but his writing and travels took precedence (Wilder May 62). He returned to Berkeley from 1913-1915, and began writing his “three-minute plays.” (Blank xiii). Wilder began to hone his writing in these short pieces, which contain many of the themes he would become known for years later. Namely, putting “ordinary” people in extraordinary circumstances. These “circumstances” stretched from being outside their own time, to being spirits or mythological creatures or figures.

Wilder entered Oberlin College in 1915, where he remained for two years. It was at Oberlin that Wilder’s early development as a playwright continued, further crafting less than full-length plays. The short play would become a major medium for Wilder throughout the rest of his career. It was when he entered Yale in 1918 that Wilder published his first short play, “The Trumpet Shall Sound,” for the Yale Literary Magazine (Blank Critical 17). It was also here that Wilder began to study archaeology, finding great interest in past cultures. This interest extended beyond cultures of the past, as Wilder often used the supernatural, as in “The Angel that Troubled the Waters,” and characters appearing from another time, as in Our Town. Wilder commented on this theme in his works in an article he composed for the New York Times in 1938. “For a while in Rome, I lived among archaeologists, and ever since I find myself occasionally looking at the things about me as an archaeologist will look at them a thousand years hence” (Wilder Preface 1). The paradox in Wilder’s work is the successful weaving together of reality and worlds that use time and place differently than reality as we know it. This theme appears in many of his works; the most evident example in “Skin” starts in Act One, where humans are living with dinosaurs during the Ice Age. This anachronism immediately sets a humorous tone for the play, yet the audience is at home because the Antrobuses, though living in the Ice Age, could be your next-door neighbors. They are everyday people put in extraordinary situations.

Wilder constantly reaches outside of his present time and place for material, and then integrates that material into the world of reality. In his shorter plays, he draws upon biblical themes, as in “The Angel that Troubled the Waters,” and “Hast Thou Considered my Servant, Job?” He calls on mythological themes, as in “The Alcestiad,” and “Centaurs,” and he rearranges time in his plays, “The Long Christmas Dinner” and, of course, “Skin” (Wilder Collected Plays).

Feeling called to religion after his time at Yale, Wilder attended missionary school and, for a short time, prepared for the priesthood. It was during his religious studies that Wilder became very aware that his true calling was writing, and he left mission work to be fully involved in literary pursuits. After finishing a Masters Degree in French Language from Princeton University in 1926, Wilder launched into an immediately successful literary career. His father suggested that he study at the American Academy of Rome after finishing Yale, and then teach. Amos Wilder arranged for his son to teach at Lawrenceville College, a preparatory school in Princeton, New Jersey. In 1926, Wilder’s first novel, The Cabala, met with favorable reviews. “Mr. Wilder is the first of the post-war crop of American writers,” wrote the New York Times, “to consider prose as something more than a medium of expression” (First 9). “The Trumpet Shall Sound” opened off-Broadway in 1926, making this year pivotal for Wilder’s literary and dramatic careers.

The review claimed: “New American Play is Quite Fantastic” (New York Times New American 15). Wilder met with more success the following year, with the publication of The Bridge of San Luis Rey.

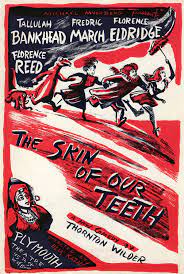

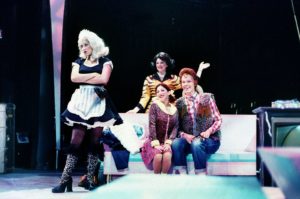

Talluluah Bankhead

In addition to winning the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1927, the New York Times claimed the book was a “metaphysical study of love,” with “exquisite style,” and “colorful substance” (Carter 7). In 1930, Wilder published another novel, The Woman of Andros, which met with more critical than commercial success. “In the chiseled perfection of its form,” said the review, “Mr. Wilder’s new book surpasses both ‘The Cabala’ and ‘The Bridge of San Luis Rey.’” (New York Times Thornton 61). Wilder published The Long Christmas Dinner and Other Plays in 1931. These are extensions of the short plays he had worked on since his days at Oberlin and Yale. These pieces serve as early shadows of Wilder’s later works for stage. For example, in “The Long Christmas Dinner,” Wilder speeds up time in the same way he would in The Skin of Our Teeth eleven years later. In this short play he spans twenty-five Christmases, and in “Skin” five thousand years. Additionally, Wilder spent time working on translations of plays, and it was in 1932 that one of his translations made it to Broadway. This was a translation from the French of Andre Obey’s Lucrece. “With its conventionalized chronicle and two baleful commentators,” Brooks Atkinson wrote, “it is an odd combination of Greek Tragedy and great-hall masque” (Atkinson Katherine 22).

Once again we see Wilder marrying his own culture with that of others. The way Wilder stretches time or changes environment is often talked about, but he also uses language to engage the audience. The most evident example of this in “Skin” is the use of Hebrew (Moses) and Greek (Homer) in the text.

In 1938 The Merchant of Yonkers premiered on Broadway, but was rather indifferently received. Brooks Atkinson stated, “being in a light-headed mood, Thornton Wilder has put together a giddy jest entitled ‘The Merchant of Yonkers.’” (Atkinson The Play 14). Though “Yonkers” did not make Wilder a major player in the theatrical world, it became the basis for The Matchmaker, which would premiere seventeen years later on Broadway and meet with much greater success. Until the time of Our Town, which premiered in 1938 on Broadway, Wilder’s literary career had overshadowed his work as a playwright. However, when Our Town opened, it met with immediate commercial and critical success. Brooks Atkinson remarked that “it will be necessary now to reckon with Wilder as a dramatist, as well as a novelist.” He claimed Our Town was a “beautifully evocative” play (Atkinson 18). To this day, Our Town is still Wilder’s most recognizable work and is his most frequently performed play. Immediately after the success of Our Town, Wilder wrote an article for the New York Times called “Noting the Nature of Farce.” In it, Wilder claims “Surely highly civilized societies can never enjoy farce, farce which depends on extreme probability” (Wilder Noting 123). Here Wilder is claiming that he uses “extreme probability” in his plays and novels to create humor and to make his point. Wilder defines “extreme probability” as “common characters in extraordinary curcumstances.” The sense one gets is that Wilder feels there can be too much “civilization,” or perhaps that our “civilized” lives have not moved us as far from our reptilian brains as one would like to think.

The Skin of Our Teeth followed Our Town by four years, opening on Broadway in 1942. The success of the play’s Broadway run came after tryouts in Connecticut and Maryland that were less than well received. After the initial critical and audience response to the tryouts, Wilder revised “Skin” for its Broadway premiere. The extent to which critical response affected his rewrites remains uncertain. (Note: The reviews for “Skin” are discussed in the “Scholars’ Response” section.) During the success of “Skin,” Wilder enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Intelligence and served in the U.S., Africa, and Italy. In 1947 Wilder received his first honorary doctorate from Yale; a second was to follow from Harvard in 1951. In 1948, Wilder published the novel, The Ides of March, which met with mixed reviews. The New York Times said: “cold, precise, artful, and quite lacking in the divine fire that glows about a major work of art” (Prescott 25). On the other side of the country and the other side of the coin was The Los Angeles Times. “Those who appreciate good writing and deep insight will cherish it as one of the distinguished author’s great novels” (Jordan-Smith 3-4). From 1950-51, Wilder held the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship at Harvard, where he also received his second honorary doctorate. At this time in his life, Wilder had lost the unanimous critical favor he had enjoyed with Our Town and “Skin.” This was to be balanced by commercial success, however, with the premiere of his next play, The Matchmaker.

When The Matchmaker premiered in 1955, critics immediately recognized it as a reworking of The Merchant of Yonkers, which had received little critical and commercial success back in 1938. One reviewer wrote:

If you expect to share the slaphappy shenanigans in

West 45th Street, you’d better run, not walk to the

box office. Otherwise, you’re going to have to wait

too long to enjoy this side-splitting house of merriment

(Coleman 38).

“Better jump in front of a subway than miss The Matchmaker,” wrote William Hawkins of The New York World Telegram and Sun (Hawkins 22). The play went on for a long Broadway run, and was made into a film in 1957 starring Anthony Perkins. Though The Matchmaker was a huge commercial and critical success for Wilder, it also signaled his last full-length play to make it to Broadway. Wilder had been conceiving The Alcestiad for two decades when it was first produced at the Edinburgh Festival in 1954. This full-length play is a reworking of the Greek Classic, Alcestis, by Euripides, and was given its tryout under the title A Life in the Sun. Critics were merciless, claiming they felt “boredom and irritation while watching it” (Hartley 305). Due to the harsh criticism, Wilder stopped his plans to take the show to Broadway the following year.

In 1961 Wilder’s early play, “The Long Christmas Dinner” was set to music by Paul Hindemith and the opera premiered in Mannheim, Germany. Wilder created a libretto for this piece and it met with favorable reviews at its opening and good response when it was performed at Julliard in the same year. “What might, in the hands of another, court cliché becomes, in Wilder’s, the touch of nature that makes us all kin, and Hindemith has responded in kind” (Music 1). Louise Talma, one of Paul Hindemith’s many students-turned-professor, was present when Wilder read The Alcestiad at a private party. She collaborated with Wilder in 1962, to create a chamber opera from this play. Wilder once again composed a libretto and the work opened in Frankfurt, Germany, to positive reviews. One critic called it a “deep and meaningful creation,” and another said it “was beautiful and interesting”(Joachim 1)(W.G. 3). The New York Times reported that the performance was met with a twenty-minute standing ovation from the “cosmopolitan audience” (Moor 25). Wilder had planned for two cycles of short plays, The Seven Ages of Man and The Seven Deadly Sins, to be the culmination of his life’s work, but he died leaving these incomplete. The Eighth Day was published in 1967 and received the National Book Award. Theophilus North, Wilder’s last novel, was published in 1973, two years before his death. Two books of essays, “American Characteristics” and Other Essays (1979), and The Journals of Thornton Wilder 1939-1961 (1985), were published posthumously.

STYLE

Wilder’s varied style is evident in his plays. For example, in Our Town he deals with American characters, moving between their relationships, past and present. By moving smoothly back and forth through time, the importance and impact of human relations is made very evident to the audience. This compression of time in “Skin” has a different impact than a play time-compressed to a lesser degree. In “Skin” Wilder uses the American family to describe the survival of the human race. The family allegorically spans five thousand years, surviving the Ice Age and World War I. “Skin,” like many of Wilder’s plays, uses everyday common characters that the audience can identify with, yet they are put into extraordinary circumstances. The best example of this is the Antrobus family living during the Ice Age, co-existing with dinosaurs. Wilder’s earlier play, “The Long Christmas Dinner,” uses non-linear time in the same way. In “Dinner” the audience passes through twenty-five Christmases, and sees family members coming to life and leaving, literally, through Death’s door. Our Town also takes time out of its linear nature through different devices: the dead talking, reflecting on the cosmic order, and the narrator breaking the fourth wall. This last causes a disruption not only in the linear time of the plot, but in the audience reception as well. “Skin” employs some of these same techniques, but on a much larger scale, regarding time and scope. For this reason, Wilder called this play “the most ambitious project I have ever approached.”

Robert W. Corrigan, in his essay on Wilder, says of “Skin,” “you never really know where the Antrobuses live, nor when they live. By destroying the illusion of time, Wilder achieves the effect of any time, all time, each time” (Blank Critical 82). Aside from the time factor, both “Skin” and Our Town make use of breaking the fourth wall, allowing characters to speak directly with the audience.

A further element of Wilder’s style is his use of historical figures and events to bring about a theme or message. In the case of “Skin,” he uses Moses and Homer to hearken back to the civilizations of yesteryear, when humankind was fighting for survival. Mankind is as fragile today as it was then, for all its vaunted “civilization.” The technique of using historical figures occurs later in the play as well, when philosophers are brought out to represent the hours of the night. Spinoza, Plato, Aristotle; these are the patriarchs of our thinking, the seminal influences of our modern thought. Wilder uses these familiar figures symbolically, as they are philosophers who were instrumental in advancing thought and civilization in their times.

THE INSPIRATION FOR THE PLAY

Wilder claimed that much of the inspiration for “Skin” came from James Joyce. This play appeared just five years after Joyce’s last major work, Finnegan’s Wake. This novel is filled with allegory and is widely known to be a book laden with encrypted messages that must be mined and deciphered. These same characteristics are to be found in “Skin,” where allegory and symbol are often used. The prose stays in the mind of the character, which can drift from the past to the present and imagine the future in no particular order. Though Wilder does not rearrange time to the degree that Joyce does, time is definitely at the whim of the allegory, as the play spans five thousand years. Wilder was attracted to allegory during Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth. In his “Notes on Playwriting,” Wilder states that “all drama is essentially allegory, a succession of events illustrating a general idea. The myth, the parable, and the fable are all fountainheads of fiction” (Blank Critical 64). The use of myth, parable, and fable could certainly be attributed to much of Joyce’s work. Finnegan’s Wake parallels “Skin;” The Alcestiad stems from Alcestis; The Matchmaker from The Merchant of Yonkers, and “Yonkers” from Nestroy’s Einen Jux will er sich Machen (Blank Critical 13). The Ides of March from, of course, Julius Caesar. One could safely say that Wilder had no problem taking inspiration from his rich knowledge of literature. The Earwickers are to Finnegan’s Wake what the Antrobuses are to “Skin.” At least one scholar has offered that the “parallels between the two families must be more than coincidence” (Wilson 167).

PRODUCTION HISTORY

The Skin of Our Teeth had its first out-of-town tryout at the Schubert Theatre in New Haven, Connecticut, on October 15, 1942. There was another trial run in Baltimore, Maryland two months later. When the play opened at the Plymouth Theatre on Broadway on November 18, 1942, the reviews were ecstatic. The play continued at the Plymouth until September 25, 1943, after 359 performances. By Spring of 1943, some of the original cast had been replaced. Gladys George had replaced Florence Eldridge in the role of Mrs. Antrobus and Conrad Nagel had taken over the role of Mr. Antrobus in place of Frederic March (Gladys 10). In 1945 the play opened in London for 78 performances with Vivien Leigh as Sabina, with husband Laurence Olivier directing. The review was telling:

Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth will have a successful

run here, though only by the skin of its teeth. There

were a good many people at the Phoenix Theatre on

the opening night complaining that they could not make

head or tail of it, and they might have easily spelled

failure for the piece at a less lucky time (Vandamm 29).

Important here is the fact that critics were very aware of World War II having great effect on the success of the play. This would be especially true in London, where the ravages of the War were felt to a much greater degree than in America. The London run was cut short when Vivien Leigh took ill later in 1945. In 1948, Olivier and Leigh revived the play and toured Australia and New Zealand, where Olivier played Mr. Antrobus (Haberman 132).

“Skin” was revived at the ANTA Playhouse for 22 performances from August 17, 1955 to September 3, 1955. During this run of the play, the American government sent the production to the Salut a la France in Paris. This production starred Helen Hayes as Mrs. Antrobus and Mary Martin as Sabina. The run received mixed reviews and had its final performance as a two-hour television show, the reviews of which were less-than-favorable. In 1955, television was a real-time medium, so the play was performed live. (Gould 49). Helen Hayes and Mary Martin reprised their roles when commissioned by the Unites States government in 1961 to return to Paris and several other countries. The reviews were ecstatic, even better than the first time. In August, the company played in Trinidad. “The Skin of Our Teeth received a thunderous ovation and seven curtain calls from a capacity audience in Queens Hall last night” (Skin 29). Then in October came the South American Tour.

Helen Hayes and the Theatre Guild American

Repertory Company performed Thornton

Wilder’s Skin of Our Teeth before a capacity

audience at the Teatro Nacional last night and

received five curtain calls (Venezuela 85).

The last Broadway revival was at the Mark Hellinger Theatre, where it lasted only 7 performances, beginning September 9, 1975, and ending September 13, 1975. This most recent Broadway appearance received poor reviews. “There have always been people besides Sabina who hated The Skin of Our Teeth,” wrote Walter Kerr. “The first company could keep Cadillacs from rolling away at intermission-time” (Kerr 99).

Off-Broadway, there was a successful television Skin transmitted live in 1983. This production was rebroadcast in 1984 from San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre, and starred Blair Brown as Sabina, Harold Gould as Mr. Antrobus, and Rue McClanahan as the Fortuneteller. It aired on WNET, channel 13 (O’Conner 38).

SCHOLARS’ VIEW OF THE SKIN OF OUR TEETH

Scholars at the time of the Schubert Theatre premiere of “Skin” had mixed reviews on the play. After the play was reworked by Wilder and made its Broadway premiere at the Plymouth Theatre, critics were behind the play, especially given the timeliness of “Skin” in deference to World War II. New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson wrote of the premiere: “The Skin of Our Teeth stands head and shoulders above the monotonous plane of moribund theatre. It’s an original, gay-hearted play that is now and again profoundly moving, as a genuine comedy should be” (Atkinson Skin 1). The main detractors of the play were those who claimed Wilder had stolen the story from Finnegan’s Wake. Just after the Broadway premiere an article appeared entitled “The Skin of Whose Teeth?” in the December 19, 1943 issue of The Saturday Review. This article was conceived and written by Henry Morton Robinson and Joseph Campbell, who had together published A Skeleton Key to Finnegan’s Wake. This inflammatory article was followed by a few others which accused Wilder of stealing his material for “Skin.”

The public did not care where the material came from, and neither did the world of research and letters. Wilella Waldorf of The New York Post, had different reasons for disliking the play, claiming it was a “stunt show” (Waldorf 8). The play was timely in regards to World War II and found success with audiences who were looking for a new form of theatre with a relevant message to their times. Lewis Nichols gave a favorable review:

A few seasons ago, Thornton Wilder increased the

stature of the theatre with Our Town and now that

November lies heavy over Broadway he has done

it again. For in The Skin of Our Teeth he has written

a play about man that is the best play the Forties have

seen in many months (Nichols 29).

Most critics agreed with Nichols, if not for the genius of the play’s construction, then for the timeliness of its appearance. Howard Barnes of The New York Herald Tribune declared “Skin” a “vital and wonderful piece of theatre” (Barnes 1-3). “Call it comedy, fantasy, allegory, or cosmic vaudeville show,” wrote Newsweek, “Wilder has contrived something provocative and stimulating” (Wilder 86-87). Alexander Woollcott was so entranced by the play, he went back to see it three times, suffering a fatal heart attack during the intermission of his third time. “Wilder’s dauntless and heartening comedy,” Woollcott wrote, “stands head and shoulders above anything else that has been written for our stage” (Woollcott 29).

How much of this positive response was due to the influence of World War II and the state of America’s collective mind at the time, is impossible to say. What can be said is that “Skin” has not received as much critical and commercial success since its first run.

The view of scholars today is that Wilder is a key figure in American Theatre and “Skin” is a play that is innovative, if not impossible to categorize. James Woolcott, who is a long time columnist for Vanity Fair, and has contributed to Harper’s and The New Yorker, writes the following about the play. “Having seen The Skin of Our Teeth and thought about it and read it, I know what I think about it. I think no other American play has come anywhere near it” (Thornton Wilder Society 1). Jill Savege Scharff writes that the play is “a hilarious, yet deadly serious, ruthless investigation of our struggle against the evil within us as we aim for moral and intellectual improvement” (Blank New 379). Mark Blankenship, who recently staged a production of the play at Yale, says it is “a vast, symbolic play about all of humanity…it is a witty, compassionate look at the struggles of a single family” (Thornton Wilder Society 1). The critics of the time the play opened to the present seem to agree on the strength of the play’s emotion. Wilder himself claimed: “the play was written on the event of our entrance into the war and under strong emotion” (Simon 273).

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SKIN OF OUR TEETH IN WILDER’S CAREER

“Skin” does not fit easily into the body of Wilder’s work. It has some of the elements of Our Town, but is more allegorical in nature. In Webster’s definition, “allegory” is “a story where people, things, and happenings have other meanings.” “Skin” fits. Nowhere else does Wilder compress time to the degree he does in this play. The span of five thousand years funneled into three hours is a stretch. The significance of the play for Wilder’s career is firstly that it uses the technique of distorting time to a much greater degree than his other plays. The second technically significant point is that Wilder uses historical figures to a greater degree than any of his other plays. To be clear: there are no other Wilder plays where so many historical figures are compressed into a three hour space. The play is also significant in that Wilder is able to merge the American ideal of family with the truth of our need to survive to see another day. This inherent need to survive and have a sense of community was explored in Our Town as well. “Skin” not only is difficult to categorize within Wilder’s body of work, but also within the canon of American Theatre. There really is no other play that is like it, especially from the time it was written. The comparisons that can be made for “Skin” come from Wilder’s earlier works, like “Pullman Car Hiawatha” and “The Long Christmas Dinner.” These two short plays share some of the same dramatic devices with “Skin,” but definitely not the scope.

Where “Skin” fits within the realm of Theatre is perhaps not as important as where it fits in time. This play spoke to Americans at a time in our history when we did feel like we were hanging on by the skin of our teeth. America has not experienced national disaster like The Great Depression and World War II since those events in our history. “Skin” was very timely and struck a nerve that would not be as accessible were it to appear on Broadway today. The proof of this is in the subsequent Broadway runs of the play which have met with less favorable critical and commercial success.

It could be argued that “Skin” does not translate well into present-day theatre, but what of Our Town? That play is still incredibly popular and is performed often. The significance of “Skin” lies in its timing and strong resonance with national events of 1942. Perhaps it is not meant to have as powerful an impact on audiences of any time as it did when it first opened. It’s significance for Wilder may be in the incredible timing of the play for the events that were affecting the world of its time. It may be significant for the hope for a better tomorrow that it represented in a time of great need for hope. “Skin” finds significance in the scope of American Theatre for its convergence of ideas and hopes in a time of great fear of what was to come. Because a work is not seen today with the same inspired gaze that it did yesterday does not make it any less a work. It has different purpose: perhaps even more noble than enduring art is art that motivates us to action in the moment needed most.

PLAY ANALYSIS

In The Skin of Our Teeth the survival of the Antrobus family is an allegory for the survival of the human race. The term “allegory” here is used to mean a story where people, things, and happenings have other meanings. The most apparent example of this would be the Antrobus family representing every American family that consisted of two parents and two children. When Mr. Antrobus makes his first appearance in Act One, he says, “Don’t let the fire go out. If the fire goes out, we die” (46). Fire is necessary for survival in the modern world, and it was absent during the Ice Age. It is not just the warmth of fire that we must have, however, it is also the fire of mind, the creative and tenacious impulse to rise to the occasion of need. The mental faculties needed to take action during human trials represent a different kind of fire. This is a fire of mind, a fire ignited inside, a fire that strives towards hope. Wilder uses the Ice Age, the Great Depression, and World War II, events that threatened life on earth, to emblematically illustrate survival on the planet. The Ice Age is used in Act One when the Antrobuses are first seen. They are living in a fantasy world where dinosaurs roam the house and co-exist with the family. They are like pets in this preposterous situation, and their presence overlaps images of the life struggle millions of years ago, with those closer to the present. The Ice Age preceded human history, but was of equal threat considering there would be no human history had life not survived. Time is irrelevant to Wilder and he uses the span of many thousands of years to pull us out of our present reality to get a message that is beyond time.

The message is that the human race always lives in the hope of seeing a better tomorrow by surviving today. The Great Depression is referenced by Sabina in Act One, as an event “we came through by the skin of our teeth” (31). The advent of World War II is reflected in Act Three, when Henry returns from the War and cannot readjust to his family. America had not declared war until after theäbombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, but Americans were conscious of the war in Europe much earlier. This awareness was greatly enhanced by the vivid mämories of World War I, just twenty-four years before. These events represent in the long term what the Ice Age represents: places in history where life on the planet could have been wiped out past the point of no return. Not letting the fire go out resonates throughout the entire play. George Antrobus is constantly striving to be civilized, to avoid wars, to stop the fighting, and to advance the world through his inventions. He wants to make a better world, and if the fire goes out, physically or metaphorically, then humanity could be wiped out by another Ice Age. Fire becomes a symbol for warmth and life and keeping away the cold of the world. Fire also symbolizes the mental fire to push forward at all costs to ensure the survival of the race. The Ice Age represents the cold, barren wasteland of a regressing world. It is the threat of a cold world that has kept life on earth going up to this point. There is the constant nagging fear that we must progress to the point that humans would not be lost to another Ice Age. This desire for progress is exemplified by George Antrobus, who is striving for a better world through his inventions and through his investment in family.

That progress, working for the furtherance of the world, is a constant theme in the character of George. On the opposite side of the coin is Henry, who seeks out destruction and the dissolution of family. He is a loner and trusts no one. Henry seeks to put the fire out by any means possible, starting with his attitude that life is not worth living. This view on life is the symbol of the fire inside dying out, and tragic events follow in its wake.

ACTION STATEMENT

The action statement “don’t let the fire go out,” occurs first in Act One. Because Act One is set during the Ice Age, letting the fire go out would mean death physically. As the play progresses to Act Two, the Antrobus family is transported to modern-day Atlantic City. Here they are on an outing, spending time together, building the strong family unit that is essential for survival. “Letting the fire go out,” in Act Two works in the sense of the family being driven apart, or driving themselves apart. George is smitten with Sabina’s Act Two incarnation, Lily Sabina Fairweather, who becomes a wedge between George and his wife. Lily Sabina lures George to her without much consideration for the effect it has on Mrs. Antrobus or the children. This is much like her character in Act One, where she is largely self-absorbed. In Atlantic City, Mrs. Antrobus reminisces about her early courtship and marriage five thousand years ago. This duration is truly “not letting the fire go out,” and is symbolic in that a marriage should be a forever commitment.

In Act Three we see the Antrobus family torn apart by war. Here “not letting the fire go out” means surviving a cataclysm of human design. If that fire dies that keeps alive our family and our relations, then the world will plunge into the darkness of war and self-annihilation. Destruction will be the result, and the human race will become a statistic. The sense one receives from Wilder is that even the most horrendous events that mankind faces begin with the personal relations in the family unit. Everything begins as the seed of relationship, and those relationships reverberate throughout the world in positive or negative waves that sooner or later must take root in action.

The entire play has the Antrobus family fighting to not let the fire go out symbolically as well as physically. The Ice Age is obviously a time when fire is needed for survival, and it is the time when fire symbolically became the instrument of continuance. The following two acts are dealing with fire of a different sort. In Act Two, there is the symbolic fire of keeping the family together at all costs, and not falling prey to the selfishness that permeates the world and creates destruction. Keeping the family together is “power in numbers,” the more people in your tribe, the better your chances for survival. In Act Three there is the symbolic fire of surviving war and rebuilding what was lost. George claims here that in times past he always had what it took to rebuild and start from scratch. After the war, he tells his wife that he has lost that vital hope. His hope was shattered and because of that, there can be no future. The seed of hope is what drives George to create a better world and it is the lack of hope that drives Henry to destroy the world that exists. So, we must not let the fire go out, because fire, symbolically, is the hope of the race and the world.

THEME

The theme of the play is the human race always lives with the hope of seeing a better tomorrow by surviving today. Wilder even said in his journals that he wanted the play to “offer the audience an explanation of man’s endurance, aim, and consolation” (Wilder Journals 51). The race sometimes moves towards destruction (Henry), where hope is lost, and sometimes progresses (George), where hope is alive and action is taken. The action statement “don’t let the fire go out,” drives this theme. Fighting to keep the fire alive is fighting for the hope of a better tomorrow. In Act One this is obvious: the Antrobus family lives in the hope that they will survive the Ice Age, keeping the fire alive. In Act Two, the family has the hope of staying together, and it is Mrs. Antrobus that keeps the fire from going out, as George succumbs to baser desires. Mrs. Antrobus claims that she married George and stayed with him five thousand years not because he was perfect, but because he was imperfect and so was she (77). These imperfections were balanced by the promise that he gave her, hence the hope. In Act Three, the Antrobus family, torn apart by war, lives moment by moment in the aftermath of that war. This tears apart the family, and like many families, it is the hope of reunification they seek. Even Henry, at the end, after his misanthropy and killing, wants just to exist and somehow find what once was alive.

TITLE

This is the meaning of the title, The Skin of Our Teeth: the human race escapes disaster by a narrow margin that it oftentimes helps create. “We escaped the Depression,” Sabina says in Act One, “by the skin of our teeth.” Life on earth survived the Ice Age by a hair’s breadth, and famines, wars, and plagues have challenged the human race since. Not letting the fire of civilization go out is the main concern of George Antrobus, but some of the other characters are oblivious that the fire could go out, and others want to extinguish it. The title, “Antrobus,” is derived from the Greek, meaning “humanity,” and George is the embodiment of humanity’s struggle to overcome its environment and itself. Sabina chooses to complain about the problems of the world, or ignore/deny them. For example, in Act One she says:

Ladies and gentlemen! Don’t take this play seriously.

The world’s not coming to an end. You know it’s not.

People exaggerate! Most people really have enough

to eat and a roof over their heads. Nobody actually

starves—you can always eat grass or something (48).

This, coming from the same woman who, in Act Three, goes to the movies when there is not enough food to feed the family. Sabina represents those people who would turn a blind eye in a time of crisis, and deny that problems exist. She shifts in character, by the end of the play, moving from denial to futility. In Act Three she tearfully states, “Oh, the world’s in an awful place, you know it is. I used to think something could be done about it, but I know better now. I hate it. I hate it” (107). Either of these attitudes, denial/ignorance or futility, give Sabina some of the characteristics of an antagonist. She works against George throughout the play.

On one level, she is the procrastinating, flippant maid, who would tear apart the family through infidelity. In a deeper sense, she is ignorant of what is really going on with world issues, and when she hears about them, she denies they exist. Sabina sums up her world-view at the end of Act Three: “after anybody’s gone through what we’ve gone through, they have a right to grab anything they can get” (109). The name Sabina comes from the Sabine women, who are the subjects of many legends. The most popular one comes to us from the Roman historian, Livy. The Sabine women told Tarpea that she could have what the women wore on their left arms, if the women were given admittance to Capataline Hill. Tarpea agreed to this, not knowing what it was the women wore. When the Sabines entered, they crushed the Romans with the shields they wore on their left arms. Sabina shares the Sabines’ trickster nature, not always having her words match her actions, enabling George’s infidelity being the most evident example.

PROTAGONIST

The principle protagonist of the play is George Antrobus. What is meant by “protagonist” here is the character that drives the play; the one who makes the plot move forward. This character, as in the case of George Antrobus, also undergoes a change throughout the play. By the end, the character is different than in the beginning, due to the events and interactions that take place during the play. In “Skin,” George undergoes a changes, starting with trying to create inventions that will help mankind. In Act Two, George can barely hold the family together due to his own lust for Sabina, which threatens life as the Antrobuses have known it to that point. In Act Three, George is back to the raw survival he experienced in the Ice Age in Act One. He experiences some prestige and affluence in Act Two, only to have it stripped away by war and circumstance. George comes full circle, falling into the war, another struggle, which he survives just by the skin of his teeth. Whether he is in the Ice Age, modern day, or the future, rebuilding after war, he is the catalyst for progress. George is the creator, who invents what society needs. He is the one who wants to rebuild in the aftermath of war in Act Three, not just buildings, but relationships. George is the character that symbolizes and embodies the fire of creativity and survival. He is always looking ahead to the future and preparing in the present for the struggle that will surely come tomorrow. George says in Act Three:

Oh, I’ve never forgotten for a long time that living

is a struggle. I know that every good and excellent

thing in the world stands moment by moment on the

razor-edge of danger and must be fought for—

whether it be a home, a field, or a country (109).

George is the protagonist of the story, but like all protagonists, he has his weakness: Sabina. Mrs. Antrobus is a protagonist as well, wanting many of the same things that George wants: better lives, a better world, safety for her family. There is a sense here of balancing out, that George’s weakness can somehow be absorbed by Mrs. Antrobus. This would vouch for the strength of the family unit, where one side could somehow cover any deficit in the other side. George is the protagonist in the sense that he is constantly moving the human race forward, whether it be through inventions, leadership, or modeling the way life should be lived for us to survive.

The simple rule in Act One of “don’t let the fire go out,” would save us during the Ice Age, had humans lived through it. The state or mental capacity of human ancestors during the Ice Age is not as important as the philosophy behind the statement. The feeling that we have deep in our cosmic selves the knowledge that we must not let the fire go out is the essential component of our survival. Straying from this means we fall into destruction, despair, and disconnection. This is what culminates in Act Three, when the family is war-torn and separate. The fire is what guards the gate, it’s the glue holding together our survival, and making possible a better tomorrow. George at once embodies hope for the future, the drive to develop, and the leadership to overcome great obstacles. He is the antithesis of Henry, and wants to create a new world, where people live in hope, not fear.

Mrs. Antrobus is a secondary protagonist to George. She is responsible for the creation of a new world as well. She keeps the race alive long enough to see the new world through maternal instinct and nurturance. During the Ice Age in Act One, the line is clearly drawn between Mrs. Antrobus and George. She is ready to burn Shakespeare and many of the other books, deep symbols of progress, if it will warm and save her children. George is reluctant to do this, because first and foremost he sees the hope of survival in furthering the knowledge of the world. Mrs. Antrobus finds the hope of tomorrow in keeping alive what we have today. Her goal is to keep the family together at all costs. This extends to a different level in Act Two when Lily Sabina threatens to disband the family. Sabina lures George away from his wife of five thousand years. George is ready and willing to go with her, when Mrs. Antrobus gives her speech on women and how sacred they are to the human race, and how if men were to truly know women, men would know the secrets of the universe (82-83). At the end of Act Three, the war is coming to a close, lights are coming on after seven years of darkness, and the hope of what used to be normal has come to pass. Mrs. Antrobus suggests to Sabina that she donate beef cubes to people who would need them most. Sabina wants them for herself. Sabina’s character is still self-absorbed in Act Three and Mrs. Antrobus is still putting others before herself. This, perhaps more than anything, makes Mrs. Antrobus a protagonist: she always puts others in front of herself. This also aligns her with George, who does the same through his inventions and his deep need to ensure not just survival, but the hope of something better.

ANTAGONIST

Henry, George’s son, is the principle antagonist. The term “antagonist” is used here to describe the character that stands in greatest opposition to the protaganist. This is the character that stands in the way and is helping to create the struggle that the protagonist is working to overcome. Henry knows there are problems in the world, and he chooses to revolt, not to create peace. Henry acts more from a place of anger and fear than of understanding. He would rather burn the house down than build it. This sets him at odds with his father. “I’m not going to be part of any peacetime of yours,” Henry says to George in Act Three. “I’m going a long way from here and create my own world that’s fit for a man to live in” (102).

The chasm between Henry and his father is deepened as a result of war and Henry states that during the war he killed many men, hoping one would be his father. This is much more drastic than their relationship in Acts One and Two. The insinuation is that war is the result of thoughtless action and the seeds of war start in the home. In Henry’s case, he is the instigator for the war through his hopelessness and his violent way of handling situations. As early as Act One, Henry is known to have a violent streak. Sabina informs on Henry, telling George that Henry threw a stone at one of the neighbors. Henry responds by saying that the neighbor boy tried to take the wheel away from him (53). This paints Henry as a selfish sort: George made the wheel for mankind, Henry wants it all to himself. Wilder likens this to the Genesis story, portraying Henry as Cain, the one who murders, who acts out of thoughtless impulse, the destroyer.

Just before Henry is likened to Cain, Mrs. Antrobus is asked about all her children and she murmurs “Abel, Abel,” the one who died (51). Henry is Cain; he is the killer, the one who seeks to destroy that flame of progress that gives the human race an edge when survival becomes an issue. In Act One, these rebellious and hateful character traits are seen in their early formation. By Act Three, these traits in Henry are full-blown, and he is the adult destroyer, the one who purposely tears down what others have built. By doing this, he kills the hope that arises through progress and surviving another day.

Sabina is a secondary antagonist in the play. Where Henry goes against George in a very strong, straightforward way, Sabina is more complacent. She is self-absorbed and refuses to see many of the events that are happening in the world. She is the seducer, the silent killer that looks appealing, the fruit in the garden that poisons. What we can walk away with regarding these two antagonist characters is that there are different types of killers, different types of destroyers. Henry charges head-on, while Sabina slips through the back door. Allowing either of these to assume control and grow brings us to war, within ourselves and within the world. It must be noted that both characters, though different in their approach, are common in the selfishness and lack of concern for others.

MOOD/FEELING

The mood or feeling of the play is both comic and serious simultaneously. For instance, there is comic irony in having dinosaurs in the living room with humans in Act One. Yet these dinosaurs fear extinction as much as the human characters. They are reluctant to go out in the cold and they crave warmth as we do. The allegorical nature of the play makes it at once comical, through suspension of disbelief, and dramatic, through the major trials the human race must suffer. It is comic due to the extreme contrast of absurdity to reality. That dinosaurs could live with humans is alone absurd, but when seen on stage, the juxtaposition would be something that audiences would have to find humorous. By playing comedy in different ways, the play is able to embellish the heavier topics such as survival, family cohesion, and the tragedy of war. Taking a different perspective on mood, one could think of the Acts as separate colors. Act One would be white, representing the blinding snow and ice mounting around the Antrobuses. Act Two is light blue, to represent the clear sky over the Atlantic City Boardwalk. This is also a lighthearted color, representing more carefree times, when the Antrobus family is not fighting to survive ice or war. Act Three is black, emblematic of the darkness of war and chaos. This is when there is no electricity and the mind is in a state of confusion and darkness as well. These would be nice moody colors to give a production designer and to give to the actors while creating their roles.

The play is very active, as if the lines are clamoring for survival like the characters. In other words, there is a deep sense of urgency from the characters, no matter what situation is presented. It is through the comedy that Wilder can focus on such heavy topics as human survival and hope over a span of five thousand years in the play. Through the comedy, a light-hearted mood is created which makes these heavy topics palatable. The play has a bittersweet feeling, and is always in the service of human survival with hope in the distance.

An interesting point about the mood and feeling of “Skin,” is that between 1942 and today, the paradigm has surely shifted regarding what is comic and what is tragic. The audiences of 1942 had just come through the Great Depression and the world was in the throes of World War II. The references to these two events would have substantially more impact on audiences of the time than audiences of today. The threat of extinction, like the dinosaurs, was literally in their living rooms. The audiences of 2005 seeing a production of “Skin” are not coming from the same perspective. Our country is neither living on the brink of desolation nor are we in the midst of a war on the scale of World War II, in terms of casualties and relative costs. Hunger, on a national scale, has not been a major problem in America since the Great Depression. Though the economy has had slumps, it has not totally crumbled as it did circa 1930.

Despite these facts, the mood of “Skin” still hits home for audiences of today because struggle will always be with the human race and fresh hope to overcome it will always be seen by some and ignored or shunned by others. What is powerful about the comedy of Wilder’s play, is the extreme absurdity of the situations. The Antrobuses are in a five thousand year-old marriage and there are dinosaurs in New Jersey. The serious part of the mood is equally strong, due largely to the poignancy of the allegory. For instance, that the human race is constantly on the verge of being wiped out, or destroying itself hits home. How do we keep getting ourselves in these situations? Why not learn from history?

Another example is Henry’s antagonism is his extreme desire to kill, even after the war has ended. Somehow we carry the seeds of our own destruction as well as creation. In times of struggle, we choose which of those seeds to water and after the trial, those memories and consequences stay with us forever. Henry is the destroyer and George, the creator. Despite the differing perspective from 1942 to the present, one thing can surely be said: the mood is at once comic and serious. It is perhaps this juxtaposition that makes “Skin” so compelling. Brooks Atkinson, one of Broadway’s most prominent critics at the time of the premiere, wrote an article entitled: “Thornton Wilder Writes a Wise and Frisky Comedy about People.” Wise and frisky: The title says it all (Atkinson).

GIVEN CIRCUMSTANCES

The given circumstances of the play involve several aspects. The first is the geographic location. Acts One and Three take place in Excelsior, New Jersey. There is no Excelsior in New Jersey, but the word “Excelsior,” is the motto for New York State. “Excelsior” comes from the Latin, “Excelsius,” which means lofty and above all else. Wilder could mean by this that the life of George Antrobus is one of lofty ideals and striving for the furtherance of the human race. When we are first introduced to the family, Wilder says, “we all want to congratulate this typical family on their enterprise. We all wish Mr. Antrobus a successful future” (29). Act Two has the Antrobus family on vacation to the Atlantic City Boardwalk. The Atlantic City Steel Pier, since 1898, was a family and tourist spot. It is a perfect weekend getaway and that is what George tries to do, get away from it all. During this Act, George is ready to leave his family for the invitations of Lily Sabina Fairweather. The name “Fairweather,” seems to imply a fair weather friend. Sabina wants to be with George because of his status, but once he lost popularity or the tide turned, she would leave him and move on to the next conquest. George is further enamored of Sabina because she was the winner of a beauty pageant that he judged. The Steel Pier is where the now-famous Miss America pageant began. As the Act progresses, the lifeguard gives us signals that the weather, ergo the state of the world, is turning bad.

A storm approaches and by the end of Act Two the characters are running off-stage, claiming “the pier is going.” This is doubtless a reference to the famed Atlantic City Steel Pier, where massive water shows and concerts were held until the Pier burned down in 1982. Donald Trump reopened the Pier in 1993, and it has been running ever since.

The date of the play is 1941. Though the date is not specifically given, several facts point to this. First, Sabina mentions how everyone came out of the Depression by “the skin of our teeth,” in Act One. This indicates post-Depression. The second fact is the heavy emphasis on war and aftermath, which would indicate World War II. The play premiered in 1942, and America became involved with the War in the same year on a large scale.

The War would have been in Wilder’s mind as he wrote “Skin,” though the play’s trial performance predated Pearl Harbor. There is an incredible timeliness in this, and it is perhaps this anticipation of things to come that made Wilder so accessible to audiences of his time. At the end of the play, Sabina says, “the end of the play isn’t written yet,” indicating that the War is not over yet. One could take this a step further and say that the war is never over, there will always be challenges for the survival of the human race (111).

There is one other clue regarding the exact year of the play. In Act One Sabina talks about her time spent in the theatre and she mentions three Broadway plays with which she was involved. The first was Rain, which premiered in 1922 and had several revivals. The second was The Barretts of Wimpole Street, which premiered in 1931 and had several runs. The last was First Lady, which opened November 26, 1935, and had only one run. This last being the most recent, the time “Skin” takes place would have to be between 1935 and when Wilder’s play first opened, early in 1942 (IBDB).

The economic environment of the play is one of survival. In the first act the characters are all freezing and burning books to keep warm. Food is scarce and so are simple items, like needles. It is under these extreme conditions that George’s inventions come about: the wheel, the alphabet, etc. It is later mentioned that Mrs. Antrobus makes her contributions to the human race as well by inventing the hem, the gore, and the gussett, as well as the “new novelty,” frying in oil. As the play progresses, the family goes to Atlantic City, and the environment changes. The environment changes with each act, but the point is that the human race faces struggle for survival despite the environment. Act One is the Ice Age, Act Two is Atlantic City, and Act Three is the aftermath of a War that could at any moment destroy the country. Wilder is saying this devastation will be the future if we continue with the War. Acts One, Two, and Three are the past, present, and future, of a human race that is barely hanging on in each situation.

The political environment is most strongly felt in Act Three, when War has devastated the world, and the Antrobus family struggles to stay together. Showing the effect of war on the family unit is political, as a statement against war and killing. The social environment is felt throughout. In Act One, society is losing its cohesion, as Mrs. Antrobus does not want to feed needy people coming to her door, to save her own family. The dinosaurs and humans live peacefully together and many inventions are being created by the elder Antrobuses that will nurture life. Act Three is a projection of the social future, if the War is allowed to continue. It is a world where the family is torn apart, where father and son are put at odds, and everyone loses.

To be considered here is the external political environment (the world) as an extension of the family political environment. Then the family political environment is an extension of the politics that are playing out in the minds of all the characters. What we think inside ourselves is where it all begins.

The religious environment is felt, but not discussed to any large degree. There is the reference to the bible: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth; and the earth was waste and void; and the darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Lord said ‘let there be light,’ and there was light” (110). This passage from Genesis is first given in Hebrew in Act One by Moses, and then reiterated at the end of the play. Then, George claims at the end of Act Three, “All I ask is the chance to build new worlds, and God has given us that” (109). George claims God’s existence and impact here at the end of Act Three.

This could be Wilder telling us that religion and belief is necessary for survival, that we are always escaping by the skin of our teeth and belief can help us in our plight. It is striking that God would be mentioned by one of the characters at the end of Act Three, as if it is only after going through struggle that one can appreciate the spiritual side of existence.

LANGUAGE

The language of the play is vernacular language. The language is sometimes silly, like when George attended the homo sapiens convention and they named him their leader. This absurd and anachronistic humor makes the viewer constantly question what is going on before fully investing in it. This is Wilder’s intention: by keeping the audience always questioning, the message that is being sent will be seen all the more. The whole play has a feeling of shaking the glass and watching the snowfall, as if there is the constant need to keep the audience awake for the message. Another device that draws out the audience is the breaking of the fourth wall. Using this device is nothing new to Wilder, who frequently made of use of it in his short plays, like Pullman Car Hiawatha. He used it most notably in Our Town, which preceded this play, opening in 1938. In Act One of “Skin,” Sabina breaks the fourth wall and then she is the character to most frequently use this device.

The language remains the same, but the effect it has on the audience goes from observation to participation. By Act Three, many characters are doing this, especially in the wake of food poisoning, where the remaining cast has to reassemble to finish the show. The effect this has is to keep the audience very awake, just by shifting from the other actors, to the audience, and back again. Then there is the whole scene at the beginning of Act Three, where the stage manager becomes a character and explains the planets as being represented by philosophers. This can be as disorienting as it is explanatory. The language stays an everyday, vernacular language of America circa 1942, but the shifting from no audience interaction to speaking to the audience makes a dramatic shift in the way the language is perceived and processed. Wilder does step away from the common use language, but it is when he is quoting. The first is in Act One, when Moses speaks to us in Hebrew:

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness

was upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God

moved upon the face of the waters (Genesis 1:1,2 KJV).

The second time is Homer’s speech from The Iliad:

Sing, Goddess, the wrath of Achilles Peleus’ son,

the ruinous wrath that brought the Achaians woes

innumerable, and hurled down into Hades many

strong souls of heroes (trans. S.H. Butcher and

Andrew Lang).

Having Homer and Moses speak to the audience in Greek and Hebrew is another thing that jolts the audience. These two passages are symbolic of the civilizations from which they derive. Both passages are also from men who were the pillars of their communities and times, they were the creators of the eras in which they lived, much like George Antrobus. The first from the Jewish heritage, describing the beginning of the world, and the second from the centerpiece of Greek literature. Both works are pillars in not only literature, but the influence they have had upon generations. They allude to something otherworldly that is beyond human understanding.

STYLE

The Style or Genre of “Skin” remains difficult to define. This is influenced by the fact that Wilder uses so many different techniques in the play. There is allegory, symbolism, distortion of time, references from ancient cultures, and anachronisms. Attaching a standard label to it, one could say it was a tragi-comedy, which could be defined as having some of the elements of both tragedy and comedy, which “Skin” does. It is tragic in the sense that the human race keeps finding itself in these situations where we barely survive, and many times we help to bring the circumstance on ourselves, war being the prime example. The play is also comic in the sense of dinosaurs on stage, a flippant maid, and the absurdity of five thousand years of marriage and life.

Wilder claimed that James Joyce had a profound influence on his writing style. Joyce’s last novel, Finnegan’s Wake, was considered by many to be indecipherable tripe and by others a work of genius. Joyce was famous for using “stream-of-consciousness,” in his writing. For our purposes here, “stream-of-consciousness” can be generally described as the narrative following a character’s conscious thoughts. That is, the plot is driven by the internal workings of the character, to which the audience is privy; it is not an external plot line.

The reader or audience is taken into the moment-by-moment process of the character’s thought patterns. There is concern for what is happening outside the character’s mind, but the meat of the narrative is mostly derived from the conscious thoughts the character is experiencing. In terms of Wilder’s writing style, this characteristic can be seen. This is not in the sense of the conscious thoughts of the characters in “Skin,” but the twisting of time throughout the play. Even though the writing stays in common language for the audience to get it, the play spans five thousand years, during which time language does not change a bit. Wilder’s language is like Joyce’s not in the sense of staying in the characters’ heads or being internally driven, but it is like Joyce in its metaphorical, allegorical, and symbolic usage. Allegorically, the Antrobus family is used to describe the plight of the family unit and how struggle is constantly knocking at the door.

This allegorical story of the Antrobus family is a scaled down version of the story of the human race. It is the story of struggle and of barely surviving one catastrophic event after the next. Symbolically, “Skin” is laden with images and archetypes of the past and present. A good example of this would be that books are the starting place for building civilization. Books are a strong symbol for hope, and George finds that his books survived the war and he comments that he will need them for civilization to be built again. The use of the Bible and the Iliad is proof that books have survived fallen civilizations and served to build the ones of today. Joyce employs these same techniques, calling upon the Bible at the beginning of Finnegan’s Wake: “Riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s.” “Skin” is as large in its scope as Joyce’s book, and stands on the shoulders of the literary giants of yesteryear. There is also the symbol of fire as a life-giving element. In its physical form, it is needed to survive the cold of the Ice Age. In its mental form, it is needed to survive the ravages of war and to overcome that part of ourselves that would destroy what we have built.

METAPHOR

A strong metaphor for this play, to put an image to the overall concept, would be a fire stoker. This is person operating a bellows to keep the fire stoked in a forge or kiln. He has to give just enough so the fire does not blow out, but he can do too much and extinguish it. George Antrobus would keep the right amount of air going to feed the flames, and he would figure out how to make an automatic, electric bellows for more efficiency. Mrs. Antrobus would blow the flames evenly and use the fire to cook and keep everyone warm. Henry would crank the bellows until it broke or the world caught fire from too much wrong intention. Sabina would leave the fire to die so she could follow a whim and question later why the fire had to go out and why it had to happen to her. Fire, like life itself, is a privilege that must be worked for, a brief miracle that wants to be forever.

AREA OF SPECIALIZATION: ACTING

The premiere performance of The Skin of Our Teeth contained a mixture of acting styles. Elia Kazan, who directed the premiere production, was entrenched in Stanislavski’s early teachings. Kazan’s influence affected the original cast, all of whom had varied backgrounds regarding styles and experiences. Kazan had been one of the original members of the Group Theatre, which started in 1931, and was an American model of Stanislavski’s teachings. For ten years the Group Theatre produced twenty productions, all with emphasis on ensemble. Lee Strasberg, Cheryl Crawford, and Harold Clurman were the original founders, and Kazan had deep relations with them. The Group Theatre consisted of 28 people who were interested in using Stanislavski’s approach to get to the internal workings of characters. This meant to experience the emotion of a character in the moment of delivery. Many techniques were used to achieve this, such as visualizations (using imagery to conjure emotion) and emotional recall (using the memory of the emotion of a past experience for a present need). The Group Theatre dissolved in 1941, just one year before Kazan directed “Skin.” Kazan’s experience with the Group Theatre definitely affected his direction of the play, much as it would years later in his film work. Kazan had graduated from Williams College and had spent time in the Yale Drama Department. It is likely he would have been familiar with Wilder’s work long before he was assigned to “Skin.”

Fredric March and Florence March (nee Eldridge) met in one of David Belasco’s production in 1927 and married the same year. March had received a five-year Paramount contract after starring in many stage productions. The Marches often appeared in productions together and their performances as Mr. and Mrs. Antrobus found great reception with critics and audiences. They returned to the stage for several projects, including “Skin” after already achieving success in Hollywood. March had won an Oscar for his 1932 performance in Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, and they both appeared in many films throughout the 1930’s. They had both started their training by getting into Broadway productions in smaller roles. Tallulah Bankhead, who played Sabina in the premiere, found no success in America at the start of her career. She moved to London’s West End, where she became the most famous actress in city during the 1920’s. She was recognized by studio producers and invited to Hollywood to appear in films. Her main influences were Broadway and the London of the 1920’s and she had come to the stage from a young age and learned the craft by immersion. Her approach to the role of Sabina was unstructured, according to Kazan, and she had frequent fights with him over how the role should be played. (Kazan 208-209). Thornton Wilder was in the Air Force during rehearsals, serving as a military staff man in California to support the war effort (Kazan 206). To Bankhead’s advantage, she had Isabel Wilder, Thornton’s sister at the rehearsals, who championed Tallulah all the way.

When Bankhead failed to appear for rehearsal one day, the producer called Kazan and told him Bankhead was having problems with the direction. She felt Kazan was purposely trying to upstage her with minor characters, animals, and dinosaurs. She told the producer that Kazan’s training with the Group Theatre, which was so different from her own stage experiences, accounted for Kazan’s seeming lack of understanding that she was to be seen and given attention at all times. Kazan came close to getting fired, this being his first major production, but fortunately for him, the producer had worked with Bankhead previously and knew she was mood swinging. After the positive reviews rolled in, the problems between Bankhead and Kazan, whatever they were, ended (Kazan 208)(Brian 123-124). Bankhead’s fear of being upstaged spilled out on the rest of the cast as well. Some, like Florence Eldridge, gave it right back to her, while others, like Fredric March, let her rave. The tension this created in the original production could be partly responsible for the edge on Sabina’s character that gave Tallulah Bankhead instant praise in the role.

Montgomery Clift, who played Henry in the production, had been on stage since he was fourteen, when he started in summer stock. He grew into larger roles throughout the 1930’s, and was influenced heavily by Kazan and the Group Theatre. His rise to fame was slowed by his refusal to “go Hollywood” early in his career. Clift studied Stanislavski’s early teachings, so his approach would have differed from those March, Eldridge, and Bankhead. His association with Kazan led him to be a founding member of The Actor’s Studio in 1947, after The Group Theatre disbanded.

Clift chose not to engage in the battles that surrounded “Skin.” “Playing the fourteen year-old Henry,” a biographer writes, “Monty managed to detach himself from the tantrums and learn from Kazan and March” (Hoskyns 43).

What can be said about the original production of “Skin” is that it had a variety of acting styles and levels of experience. Add to this some fiery temperaments, and the hard energy needed to do a play about the survival of the human race is created. What can also be said about the original production is that it was performed in a world that no longer exists. It was a world very ready to receive the message that “Skin” had to give. Presenting this play today would mean giving it to an audience that is not living with the fear that the country may not be here tomorrow. What does remain constant in the play is the fact that even though we may sometimes feel alone in the universe, as Henry does, we are, by paradox, social creatures. We want strong family connections and even if we are not concerned with survival per se, we do live in hope that our tomorrows will be better and better.

Choosing a character to play in “Skin,” it would have to be Mr. Antrobus. I’m too old to play Henry and I identify with George Antrobus. I’m an optimist and I believe in the hope of a better tomorrow. Also, like George, I believe I help create that tomorrow. I have been married, so I can pull from that emotional memory. I would start the character of George the way I do every character, asking “what is it I want?” This is the motivation of the character, which needs to be explored before action is taken. There is always several layers to this which have to be gleaned from the text, rehearsals, interactions with the other characters, and self-discovery.

I would then move on to asking “how do I get what I want?” This is the action of the character; this is what I have to do in the physical world to follow my motivation. Then I have other questions I ask my character: “What do I really get if I get what I want?” “How does getting what I want affect those around me?” “What happens if I don’t get what I want?” I would also consult with the director on the overall metaphor for the play, so we would have the same image and intention for what we were creating. Hopefully, the rest of the cast would want this approach. Having a good idea of what the set design entails serves me well in creating a role. What I mean by this is being familiar with where walls, doors, windows, and furniture are positioned even before they are created and placed. This strengthens my blocking and my action. I like to change my emphasis on text during every rehearsal, so I am really getting to the meaning of everything that is said. This apply to my actions as well: not just accomplishing an action, but asking what how that action needs to be carried out to support the play and move the plot forward. Spending time with the cast outside of the production is always good for me, when possible. By knowing the cast on a personal level, outside of our characters, I more easily empathize and play with them through familiarity. I return to the text for answers often, to find more of the essence of character and meaning. Usually, good text and direction will lead me through these questions and give me answers. Sometimes I may not like the answers. Art imitating life again.

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atkinson, Brooks. “Frank Craven in Thornton Wilder’s ‘Our Town’; which is the

Anatomy of a Community.” The New York Times. 5 Feb., 1938. Pg. 18. This

article verifies the critical success of Our Town.

Atkinson, Brooks. “Katherine Cornell Presenting Thornton Wilder’s Translation

of Andre Obey’s ‘Lucrece.’” Review. The New York Times. 21 Dec., 1932. Pg. 22.

Wilder’s skills rest not only in his original works, but in translating the works

of others. This article strengthens this case.

Atkinson, Brooks. “The Skin of Our Teeth—Thornton Wilder writes a Wise and

Frisky Comedy about People.” The New York Times, 22 Nov., 1942. Section 8,

page 1. Critical review of the play.

Atkinson, Brooks. “Thornton Wilder Adapts an Old Farce Into a Jest Entitled

‘The Merchant of Yonkers.’” The New York Times. 29 Dec., 1938. Pg. 14.

This article shows that “Yonkers” did not have the same reception critically

that Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth did.

Barnes, Howard. “A Major Event in This or Any Season.” Review. The New York

Herald Tribune. 29 Dec., 1942. Sect. 6, 1-3. “Skin” review.

Blank, Martin. Critical Essays on Thornton Wilder. G.K. Hall and Co. New York, NY,

1996. This is Martin Blank’s earlier collection of Wilder essays. There are

three of the eight essays of use here. “Three Allegorists: Brecht, Wilder, and

Eliot,” by Francis Fergusson; “Thornton Wilder and the Tragic Sense of Life,”

by Robert W. Corrigan; and “Symbolist Dimensions of Thornton Wilder’s

Dramaturgy,” by Paul Lifton.

Blank, Martin, Dalma Hunyadi Brunauer, and David Garrett Izzo, ed. Thornton Wilder:

New Essays. Locust Hill Press: West Cornwall, CT, 1999. This comprehensive

collection of essays on Wilder spans his career as novelist and playwright.

There are two essays in this newer collection to reference. The first is Douglas

Wixson’s “Thornton Wilder and the Theatre of the Weimar Republic.” The

second is “The Skin of Our Teeth: A Psychoanalytic Perspective,” by

Jill Savege Scharff, M.D.

Brian, Denis. “Tallulah, Darling: A Biography of Tallulah Bankhead.” Macmillan

Publishing Co., Inc. New York, NY, 1972. Pgs. 123-124. Secondary source

for the Acting portion, as it speaks “Skin” behind-the-scenes.

Bryer, Jackson R., ed. Conversations with Thornton Wilder. University of Mississippi

Press: Jackson, MS, 1992. This series of conversations with Wilder sheds light

on his intentions with Skin of Our Teeth, and his plays in general.

Cardullo, Bert. “Whose town is it, anyway? A Reconsideration of Thornton Wilder’s

Our Town.” CLA Journal. Baltimore: Sept., 1998. Vol. 42, iss.1, pg. 71.

This article provides insight into how changing cultural views shape the

way Wilder’s plays were viewed in their beginnings contrasted with today.

Carter, John. “Mr. Wilder’s ‘Bridge of San Luis Rey’ is a Metaphysical Study of

Love.” The New York Times. 27 Nov., 1927. Pg. 7. This review speaks to the

strength Wilder’s writing had early in his career, with audiences and critics.

Coleman, Robert. “Robert Coleman’s Theatre: The Matchmaker a Hilarious

Comedy.” Review. The New York Daily Mirror. 7 Dec., 1955. Pg. 38.

Placed here to show the extreme critical and commercial success of

The Matchmaker. “First Novel of a New American Stylist; The Cabala.”

Review. The New York Times. 9 May, 1926. Pg. 9. This review is referenced

to show Wilder’s early success in the literary world.

Gilder, Rosamond. “Broadway in Review: Old Indestructible.” Theatre Arts. 27

Jan., 1943. Pgs. 9-11. “Gladys George Absent: ‘The Skin of Our Teeth’ Star

Reported Ill.” Article. The New York Times. 31 Aug., 1943. Pg. 10. Confirms

the changing of the original cast during the initial run.

Gould, Jack. “The Skin of Our Teeth: Wilder Play Offered in All Its Confusion.”

Review. The New York Times. 12 Sept., 1955. Pg. 49. Gives review for

the 1955 run and the live television performance of that same year.

Haberman, Donald. “Preparing the Way for Them: Wilder and the Next Generations.”

Critical Essays on Thornton Wilder. G.K. Hall and Co. New York, NY,

1996. Verifies the London premiere and run of “Skin” with Laurence

Olivier and Vivien Leigh.

Hartley, Anthony. “Contemporary Arts-Festival Blues.” Spectator. 2 Sept., 1955.

Pg. 305. This review shows the decline of Wilder’s commercial success

after The Matchmaker.

Hawkins, William. “Matchmaker is Delightful.” New York World Telegram and

Sun. Review. 6 Dec., 1955. Pg. 22. This further establishes the success of

The Matchmaker.

Hodge, Francis. Play Directing: Analysis, Communication, Style., 5th ed. Allyn

and Bacon: New York, 1999. The model for the analysis portion of the

written assignment.

Heinz, Joachim. “There are No More Miracles.” Review. Die Welt. 3 March, 1962.

Pg. 1. Here to show Wilder’s immense and diverse influence on many arts.

Hoskyns, Barney. Beautiful Loser: Montgomery Clift. Grove Press, New York, 1991.

This biography of Clift details his career, and has a section of “Skin,”

and his role as Henry.

Jordan-Smith, Paul. “Books and Authors: Julius Caesar Lives Again in the Pages

of a Graphic Novel.” Review. Los Angeles Times. 22 Feb., 1948. Pgs. 3-4.

Goes to show the mixed critical response of Wilder’s later works.

Kazan, Elia. Elia Kazan: A Life. Random House: New York, 1988. This

autobiography gives insight into Kazan’s direction for “Skin” as well

as anecdotal material about the actors and the production.

Kerr, Walter. “A Revival of Skin That Lacks Teeth.” Review. The New York Times.